Poems by Barbara Lee

Archives: by Issue | by Author Name

The Inspired Pen of a Wildlife Warrior

by Barbara Lee

Barbara lives close to a newly restored wetlands that connects to the Willamette River in Eugene, Oregon. Chinook fingerlings are sheltering in these wetlands for the first time in 60 years. She also works as a seasonal volunteer in Yellowstone National Park in the corner where the Yellowstone River, the Gallatin Range, and the Gardiner River come together.

Oh, puny Man, wouldst thou atone

for years of swelling ego heart?

Go tread the mountain-top alone

and learn how very small thou art.

from “Wild West, Spell of the Mountains”

Surrounding Yellowstone National Park’s Lamar Valley are mountains with names like thunder claps: Druid. Abiathar. Baronett. The Absarokas. Among these peaks is little known Mount Hornaday, bearing the plain name of a man who battled for decades to save America’s vanishing wildlife. William Temple Hornaday was famous in his time, but now, like the mountain, receives little attention.

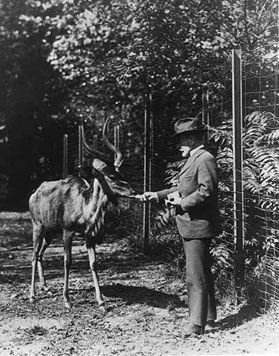

Born in 1854, William Hornaday was a prominent zoologist who during his long life was also a taxidermist, hunter, museum director, and prolific writer. His great passion was the protection of vulnerable animal species, and like his good friend Teddy Roosevelt, a love of hunting and collecting evolved into action to halt the ongoing slaughter of vast numbers of wild animals.

One way that Hornaday brought wilderness to the attention of the Victorian era public was through unabashedly melodramatic poetry. The author placed readers on snowy crags where creatures were brave, even gallant, in the face of nature’s extremes:

from “The Rocky Mountain Sheep”

His home around the mountains frowning crest,

Where lines of rugged rock stand forth,

Where Nature bravely bares her breast

To snowy whirlwinds from the north.

High in the clouds and mountain storms,

Where first the autumn snows appear,

Where the breath of springtime last warms

There dwells my gallant mountaineer.

William Hornaday saw himself as a warrior on behalf of all threatened wildlife, but saving the bison from extinction became his signature effort. By the turn of the century very few of the animals remained, and in 1905, Hornaday and Teddy Roosevelt formed the American Bison Society in order to prevent the disappearance of the species.

Efforts to protect, re-introduce, and increase the number of bison gradually succeeded. One well-known project took place in Yellowstone, home to the two dozen animals that made up the last wild herd. In 1907, the herd was moved to a newly built buffalo ranch in the Lamar Valley to ensure the animals’ survival and form the nucleus of a growing population. Hornaday’s fierce verse asked what kind of society would slaughter the bison to the very brink of extermination:

“The Buffalo”

We went at the millions outrageous, thinking they always would stay,

and before we knew we were wicked, they totally vanished away.

William Hornaday’s old-fashioned style hid a good deal of modern content. A century ago, Hornaday’s poetry argued the radical philosophy that wildlife was more than just a resource to harvest, and that a landscape robbed of animal life was soon desolate. Hornaday’s tribute to the pronghorn antelope pictured a setting where greed and ignorance brought on the loss of every living creature down to the last wolf.

from “The Antelope”

The rifles and greedy old game-hogs,

the barbed wire fences and snow —

I shore hate most awful to lose him,

but I guess that he's bound to go.

No living thing in sight, no creature near

To break the desolation of the scene.

The black-tailed deer have fled before the gun.

The antelope were slaughtered, one by one.

The last lone wolf lies crouched

in hungry fear in yon ravine.

In Yellowstone, the Lamar Buffalo Ranch still stands in the valley ringed by peaks, but the log cabins and bunkhouse are now used for educational seminars. Most people wouldn’t guess that this quiet spot was the location of one of the most famous wildlife projects in the country’s history.

President Frankin Roosevelt recommended that a Yellowstone peak be named after Hornaday to honor his work to protect America’s vanishing wildlife, but the naming did not occur until 1938, the year following Hornaday’s death. It’s too bad. You can imagine the old Wildlife Warrior gazing at Mount Hornaday and out over Lamar Valley, now populated by grazing bison, and then penning a verse something like this one:

From “Spell of the Mountains”

Toil to the top of cloud-kissed peak

and see vast seas of mountains roll.

Then feel great things thou canst not speak

Because of smallness of the soul.

Further reading...

Many of William Hornaday’s books are still available, including several that are free in electronic form. Poems in this article are from Old Fashioned Verses by William T. Hornaday (1919).

There is a recent biography of William Hornaday, Mr. Hornaday's War: How a Peculiar Victorian Zookeeper Waged a Lonely Crusade for Wildlife that Changed the World by Stefan Bechtel (2012)

© Barbara Lee